The product that doesn't exist

Designers, product, and engineer are all guided by the "Product Ideal." The problem is, they're all seeing a different one.

We operate under the illusion that we're all working towards a single, shared vision of the product. The reality is, we’re not. The designer, the product team, and the engineer are each guided by their own "Product Ideal" - a perfect, internal vision of what the product should be, seen through their own perceptual lens.

This perceptual gap is the source of our most expensive problems: the misaligned meetings, the frustrating compromises, and the hurt egos. This article is an attempt to make those invisible ideals visible, exploring a shared language to diagnose this friction and begin building an ontology for the practice of digital product design.

The three ideals

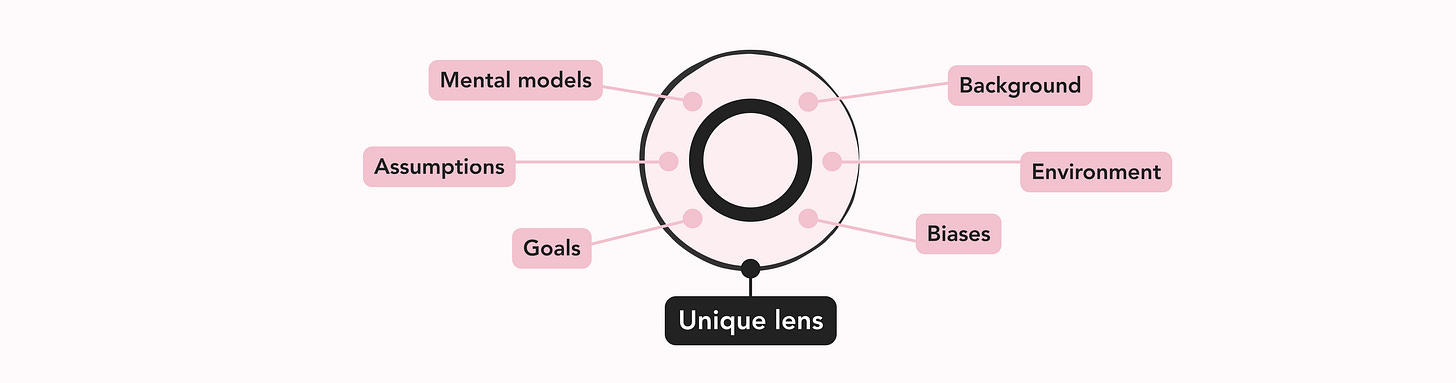

The friction we feel is not random. It’s a systemic clash between three powerful, well-intentioned, yet fundamentally different ideals. Each role on a team is trying to build their own version of a perfect product. An ideal seen through a unique lens, a view permanently laminated with our personal biases, our background, and our core goals.

The designer's ideal is an empathetic utopia

For the designer, the ideal product is an extension of the user. It’s a solution that perfectly meets their unique needs. As an example, imagine a product connected to every digital platform you touch, one that is also aware of your physical world. It adapts its interface to what you need right now, reducing clicks because it already knows your habits or changes contrast to adapt to your surroundings. Its core value is empathy at scale, creating a seamless, assistive experience.

The product team’s ideal is a value engine

For the product team, the ideal product is an engine for identifying and capturing value. It understands user behaviour so well that it can pinpoint exactly how to make their work faster or their tasks easier. This insight isn't just for selflessness. It’s an opportunity to quantify the value provided and, in a business context, sell that value at the highest possible price. Its core value is the monetisation of insight and efficiency.

The engineer's ideal is a stable system

For the engineer, the ideal product is stable, predictable, and robust. It is a system that does not break. It doesn’t create unexpected bugs, security risks, or other technical vulnerabilities. It is a world of order, logic, and integrity.

The inevitable collision

What happens when these three powerful ideals meet in the real world? Compromise. I once argued for a complete rebuild of a component because its underlying structure was causing major issues for users with assistive technologies. My ideal was a seamless experience for this subset of users. The product team’s ideal was not to invest more into a somewhat useful feature. The engineer’s ideal was not to redo frustrating work.

The result was a functional compromise that landed somewhere in the middle. It fell short of the truly seamless experience I had envisioned, yet it still required effort and a budget. This is the daily reality of a product designer’s work.

Product Ideal vs. Perceptual Gap

To navigate this constant friction, I've started to map the phenomenon. My goal is to investigate it clearly and develop a shared language that can help us navigate these different realities. The two most important landmarks on this map are what I refer to as the "Product Ideal" and the "Perceptual Gap."

The "Product Ideal" is the North Star for your project. The concept is inspired by Plato’s Theory of Forms, which suggests that for everything in the physical world, there is a perfect, uncompromised "Form" in a conceptual space. Our "Product Ideal" is this Form. The Ideal itself isn't the problem. The problem is that each team member sees a different piece of it, through their own context and biases.

The space between these fragmented visions is the "Perceptual Gap." Design pioneer Don Norman wrote extensively about the gap between a designer’s conceptual model and a user’s mental model. I believe a similar gap exists within our teams, long before the product ever reaches a user. This gap exists because each role has its own goals, biases, and a unique understanding of the project's limitations and requirements.

Naming these concepts is more than just an academic exercise. It’s a tool for building what Harvard professor Amy C. Edmondson calls "psychological safety." When you can point to a "Perceptual Gap," you neutralise the conversation. The conflict is no longer a personal argument between you and a colleague. It's an objective discussion about the space between your team's different "Product Ideals."

Using this language transformed how I navigate my role. It allows me to create the psychological distance I need to depersonalise feedback. An engineer’s critique is no longer an attack on my ego, but rather a vital insight into the conflict between the Ideal and the system's architecture. I no longer feel like I am challenging a PM’s authority. I am questioning how a business requirement honours the Ideal. It shifts subjective arguments into a collaborative effort to solve a systemic puzzle.

Creating a shared map

To navigate these challenges, I realised I needed a better map. Not another process framework like Design Thinking or Lean UX, which are excellent at describing how we work, but something that defines what we work with. This series is my attempt to create that map, for myself first, and to share it with you as I go.

Through personal experience and research, I am contemplating what an ontology for digital product design truly is. The term "ontology" has a formal meaning in computer science, but I am using it in its more foundational, philosophical sense: an exploration of the nature of being within our specific world. While academic ontologies of product data exist, there seems to be a gap in the literature for a human-centric, psychological ontology of the practice of digital design. This is the gap I want to explore.

I hypothesise that if we can create a shared map of our world (with the ideals, the hidden logic, and the human realities), we can build a shared language. This language could be the scaffold for further debate and defining the philosophy around the digital spaces we find ourselves in.

Conclusion

My journey is to map the territory of our work, not just for myself, but to build a more resilient and empathetic way of working together. This exploration starts with a shared language, but hopefully ends with better products.

The most important product your team will ever work on is the one that doesn't exist: your shared understanding of the Product Ideal.

You may think the hardest part of design is stakeholder management. But what if the root of your disagreements isn't just a matter of perspective, but is built into the very structure of the product itself? In the next article, I will attempt to deconstruct the product ideal to uncover the source of many design challenges.

What is the biggest "Perceptual Gap" you're currently facing on your team? I'd love to hear your story.